Exhibition: Out of Time (2023)

Text by Lucas Odahara

It took us long to talk about our families. Living mostly outside of what they are willing to imagine, the path to this topic can be a difficult one. But when we did talk about it, it wasn’t small talk. We were speaking from the edge of their gaze. That’s how it usually felt like. Family, as in the bloodline system, is a precarious image. We can so easily ruin it, or in fact, we can so easily remind this image of its ruinous grounds, of its temporality. Maintaining it as an eternal, sturdy institution, entails what every attempt to create perpetuity does: conflict, violence, exclusion and perhaps a very particular notion of care. And we’ve been always aware of that. Rob’s practice and all the conversations we had throughout the years in Berlin traverse these spaces. In his work, a garden, like family, exists in the same conflicting grounds of care, interdependency and the dream of permanence.

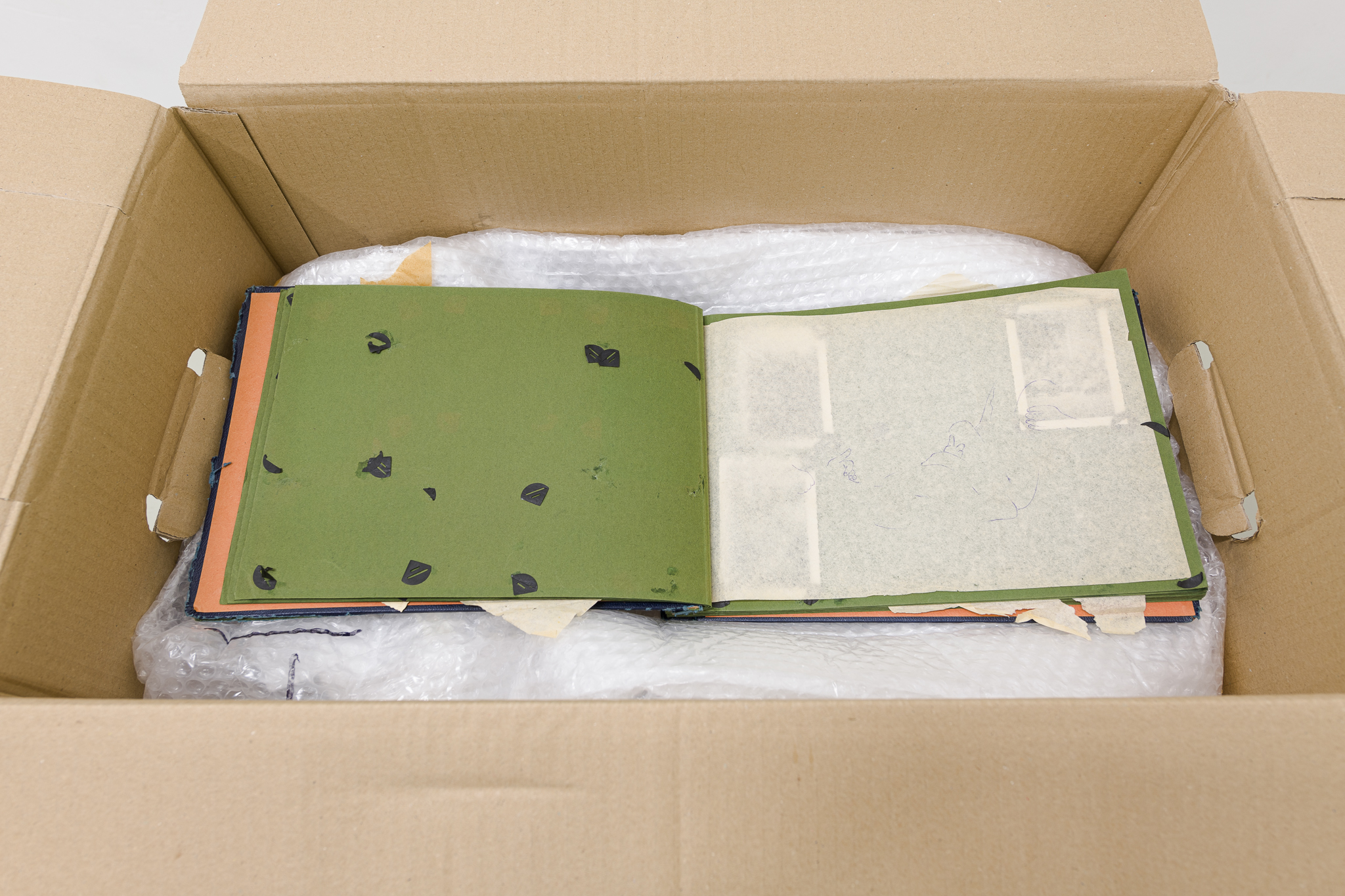

The family albums in Rob’s piece ‘All the things I didn’t tell you’ were found in Berlin. While one can hardly see the photos within its pages, one’s attention is driven towards the in-between papers that protect the photos. On them, Rob made drawings of hands touching, holding, pinning down. They could be seen as traces of bodies having sex, supporting each other or even forcing themselves onto the albums’ pages. ‘Points of Pressure,’ Rob told me recently. And I can see it – hands pressing against bodies, the pen against the thin aged paper, family portraits pressed against each other. But the points of pressure that Rob’s work actually addresses are not visible. It’s a kind of pressure that exists between what is photographed and what has been removed. It’s what crosses at the edge of the gaze of those in the photos. It’s the shadows they see in the margins of their sight but make sure their eyes don’t follow. It’s what is at the edge of the park, out of the frame. Rob’s drawings separate the albums’ pages while gently touching all the photos in them. It touches so they don’t touch each other, don’t stick together towards decay. It’s a form of tangential care and participation in a well known narrative – black and white photos in carefully curated albums, cardboard boxes filled with Kodak prints, oil paintings of the royal family. The story of the bloodline is one of repetition, reproduction and removal. It documents above all property and the limits of wealth. It’s an old story – one paints the land and who owns it. It can often be confused with an accurate experience of time. Painting after painting of royal generations in museums, album after album of generational photography in one’s family home. Rob’s show is ‘out of time’ because it exists outside of the time described above. It’s about a kind of time and body that evade exposure in the first place.

Both the drawings and the photographs on the walls look at these spaces outside the frame – the spaces for sex, for understanding one’s own body after being removed from the picture, for caring outside bloodlines, for safety. And Rob’s work does not expose that which has been removed. It offers traces, perhaps the desire to see. And desire is the axis that separates, and which drove the pressure on Rob’s pen in the first place. Looking at his photographs and drawings makes me feel like I have been in these spaces, like my body remembers. I don’t see myself, but I see my gaze in Rob’s gaze and his gaze on my gaze and so many other crossed gazes in similar spaces, and it’s a story I know. And it feels familiar.